She Can Call Me Tom

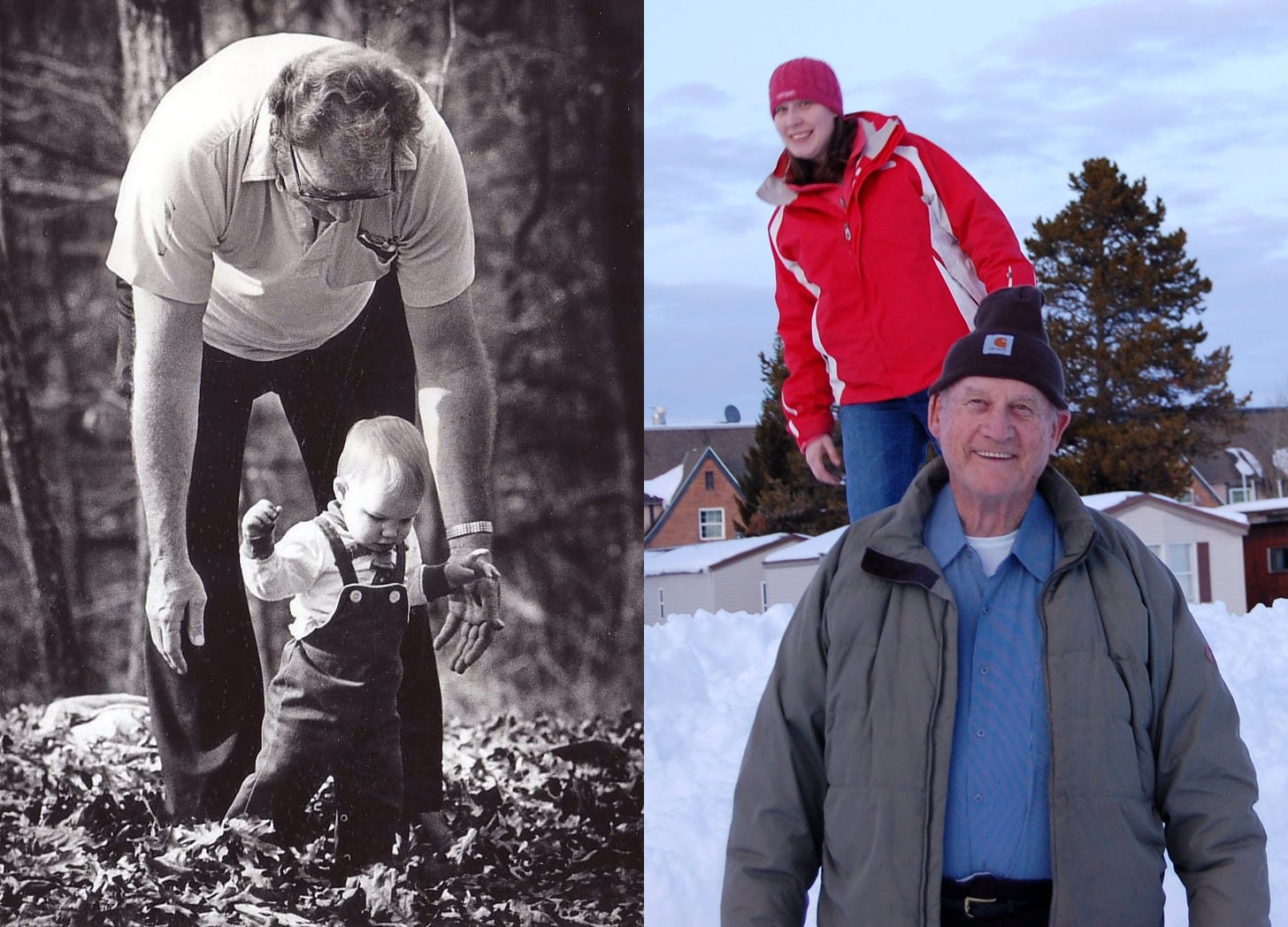

My grandpa had a heart attack this week, and all I can do is write about it.

My grandpa was only 41 years old when I was born, not a gray hair on his handsome head. He had broad shoulders, strong hands, that kind of laugh that sounds like a storm about to blow out the windows. He’d been an all-state football player as a teenager, and I think in his heart he still kind of was, but he loved my grandma more than the trophies and the band and the fans yelling his name under the shining lights, so he married her just as soon as he could. They’d met at a sock hop, a real one with poodle skirts and bobby socks, where you had to leave your shoes at the gym door and pay twenty-five cents to get them back.

He said my grandma was the prettiest woman he’d ever seen, and he wasn’t wrong about that. Brown hair, brown eyes, a face like an angel. But he was no slouch either. He did the work of two men at the carpet mill when it wasn’t football season, and he had the biceps to prove it.

“I’ll call you,” is what my grandpa told my grandma when they finished dancing at that sock hop where they met. She laughed and said, “Oh yeah? What’s my number?”

If you’d asked my grandpa how to raise a little girl when I was born, he’d probably have said he didn’t have a clue. He was a man’s man who fathered three sons. My mom asked what kind of nickname he wanted, the day I popped out into the world. She asked what I’d be calling him. He said, “She can call me Tom.”

What Tom didn’t know — but God certainly did — was that to be part of the village that raised a girl like me, he needed experience with formidable women. I never met the woman who raised him; she was his aunt. But I know enough to know she took in another mouth to feed on a tiny farm in south Georgia during the Great Depression, and she raised Tom like he was her own son. Tom’s sister, my Aunt Opal, she didn’t follow anybody’s rules. And she certainly didn’t get married young. No, she got herself a job at Sears in downtown Atlanta and worked her way right up to managing the whole entire second floor. Aunt Opal and her best friend traveled across the country; they went to California, which might as well have been the moon for a single woman in the 1960s. And, well, I already told you how my grandma handled Tom at that sock hop.

Those were the women in his life. And then he had me.

Me and Tom spent a lot of time watching each other. I watched him clean fish, clean the grill, clean the leaves out of the pool drain. He watched me throw a tennis ball against the side of house, over and over and over, hours at a time. Every so often, he’d walk over and give me a tip. Keep your shoulder loose, keep your elbow bent, lead with your hips. Good. Good. That-a-girl. One time I tried to use a real baseball in my training drills and I knocked a window out of the garage. I sat on the edge of his little single-motor fishing boat and watched him fix it. I said I was real sorry. I offered him my allowance to pay for however much five dollars would cover on a window repair, and he laughed and said, “Ask your daddy how many windows he broke growing up.” (Between three boys, probably a whole lot.)

When I moved on from baseball to basketball in high school, Tom didn’t have a lot of tips for me, but he drove all over the state to watch me play and when my grandma sent me to his closet one time to grab a jacket for him, I found a shelf that had every single newspaper clipping from every single game I’d ever played in.

I got the feeling, growing up, that most everybody wished I was a little bit different. That I’d wear more dresses, that I’d curl my hair, that I’d be a little bit more quiet and a little bit less weird and maybe even bring home a boyfriend. Everyone was always telling me to slow down, to look out, to be careful, but when I came limping in with another thumb hanging weird or a lump on my noggin or blood soaking the knee of my pants, Tom would just say, “Girl, grab the Bactine and come over here. You’re lucky, when I was growing up, we’d just spit on something like this and hope for the best.” If I was crying, he’d inspect it even closer and say, “Do you think we should cut it off?” And it always made me laugh away my tears.

Tom didn’t get much of an education growing up so poor when he did, but he worked his way up to being the best meat cutter in the country and he’s read the Bible, cover to cover, at least 50 times. He taught himself how to play the violin when he was in his 70s. He wrote a book in his 80s. Before he let the outside tomcat move inside, he built him a heated house with steps, right outside the kitchen window so they could both stay checking in on each other.

We went snowmobiling in Yellowstone National Park when he was in his 70s too, just me and him and my grandma. We stopped at the state border, the snow up to our chests, the highest any of us had ever seen. He pulled out the camera and said, “Heather? Why don’t you tackle your grandma.” She hollered so loud when I piledrived her from Montana into Idaho, his laugh echoing off the mountains.

When I brought a boy home for the first time, Tom watched us play catch in the yard. After the boy left, Tom said, “He doesn’t throw like you.” I glared at him and said, “Like a girl?” He glared back and said, “Like a ball player.”

And when I sat on the couch and cried and cried and cried and told my grandparents I’m gay, he said, “Baby, I know. Let’s have some pancakes.”

As I’m writing this, I’m 45 years old, four years older than my grandpa was when I was born, and he’s in the hospital getting ready for surgery in the morning. He had a heart attack earlier this week. A small one, they say. A mini one, maybe. Whatever that means. My family’s been texting all week, numbers and numbers and anatomical words, keeping me in the loop all the way up here in New York City. All of them are much smarter than I am about science things, so I’m relying on their love and interpretations. But I do know one thing about Tom’s heart that no one has to explain: he’s never stopped loving me, since the day I made him a grandpa.

And of course he hasn’t. He was raised by stubborn women and he helped raise a stubborn woman. He made up his mind to love me the day he made up his mind that I would call him Tom. Nothing has ever changed that, and nothing ever will. Tom Hogan told my grandma he would call her after that sock hop. He told me I’d always have a home at his home. He told me nothing could dim the light of his love for me. He’s always been solid. He’s always been true. His broad shoulders have carried me and my whole entire world.

I hear your southern in this more than many of your other essays. And I rightly like it! As always, you made me cry tears of joyness several times, and in return I’ll be praying for Tom from SC to GA this morning.

And now I'm crying. What a beautiful essay about a beautiful relationship. I'll be thinking good thoughts for you and your grandpa and your family.